This discussion will focus on the cross-pollination, interconnectivities and interdisciplinary theories of Big Data with respect to business models. The core question would be how do we define business models? A throwback to the 1950s revealed the popularity of the combination of the firm’s revenue source identification, customer base identification, product identification and financing details, as the overall strategy to optimize operational profits, has grown substantially in relation to the decreasing cost and growing ubiquity of technology. Within this continuum, phraseology was adopted by academicians referred to as the “business model.” This combination has had its foundation steeped in the depths of transaction cost economics; and has evolved to an established strategic component used to unify management and information systems. Essentially, business models have been used to characterize the modus operandi of a business in terms of (a) delivering value to the customer, (b) attracting customers to pay for value, and (c) transforming those payments into profit (Teece, 2010). To some extent, it was proposed the type of legal rights for sale has been fundamental to the model’s typical commercial offering. Among these rights were the sales of: (a) the ownership of an asset, (b) the use of an asset, and (c) the potential matching of the asset. Weill, Malone, D’Urso, Herman and Woerner (2005) have identified four basic business models as derivatives of these legal rights. The models were the creator, the distributor, the landlord, and the broker. Concomitant with the business models were 16 classic exemplars that included the manufacturer, the entrepreneur, wholesaler-retailer, financial trader, and several landlord and broker archetypes. Weill et al. (2005) noted that business models based on the sale of the use of the asset were more profitable than those based on the sale of ownership of the asset.

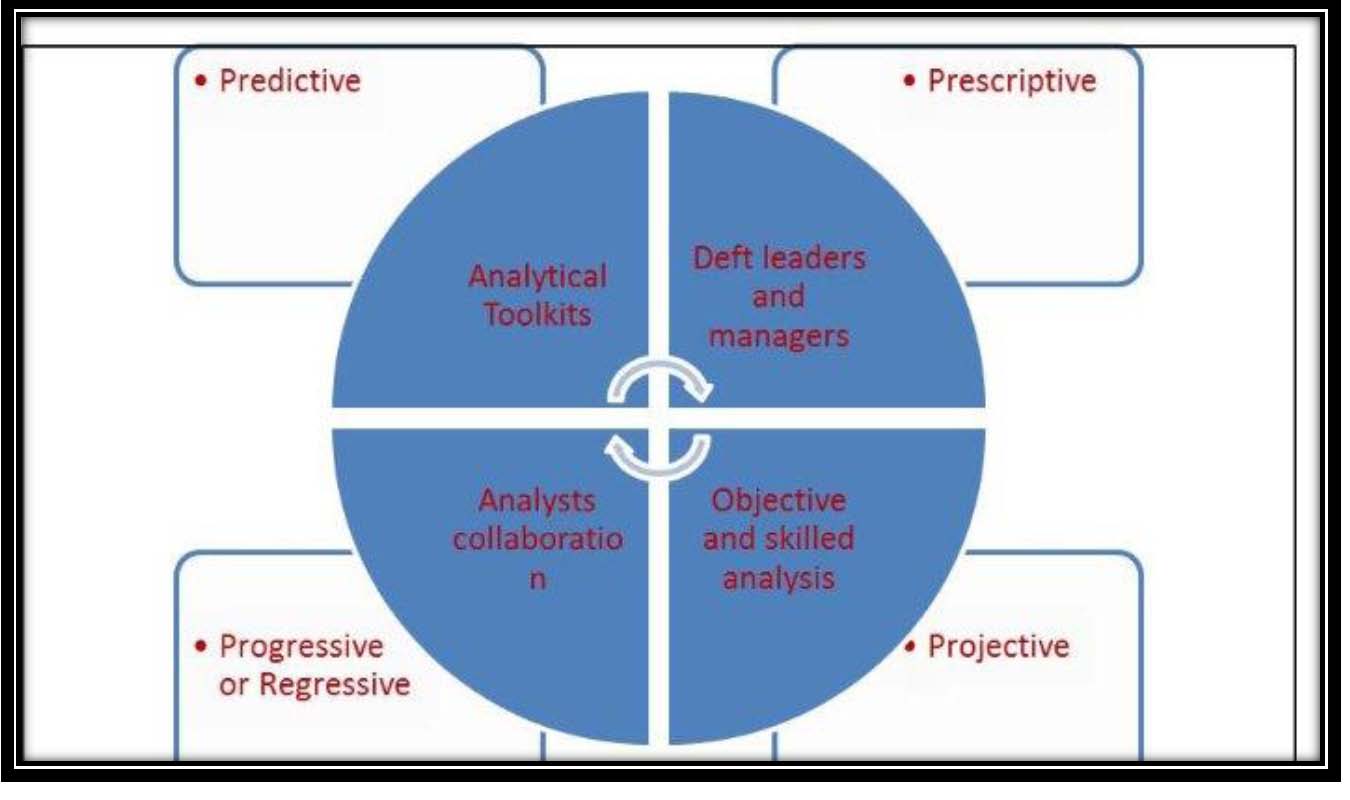

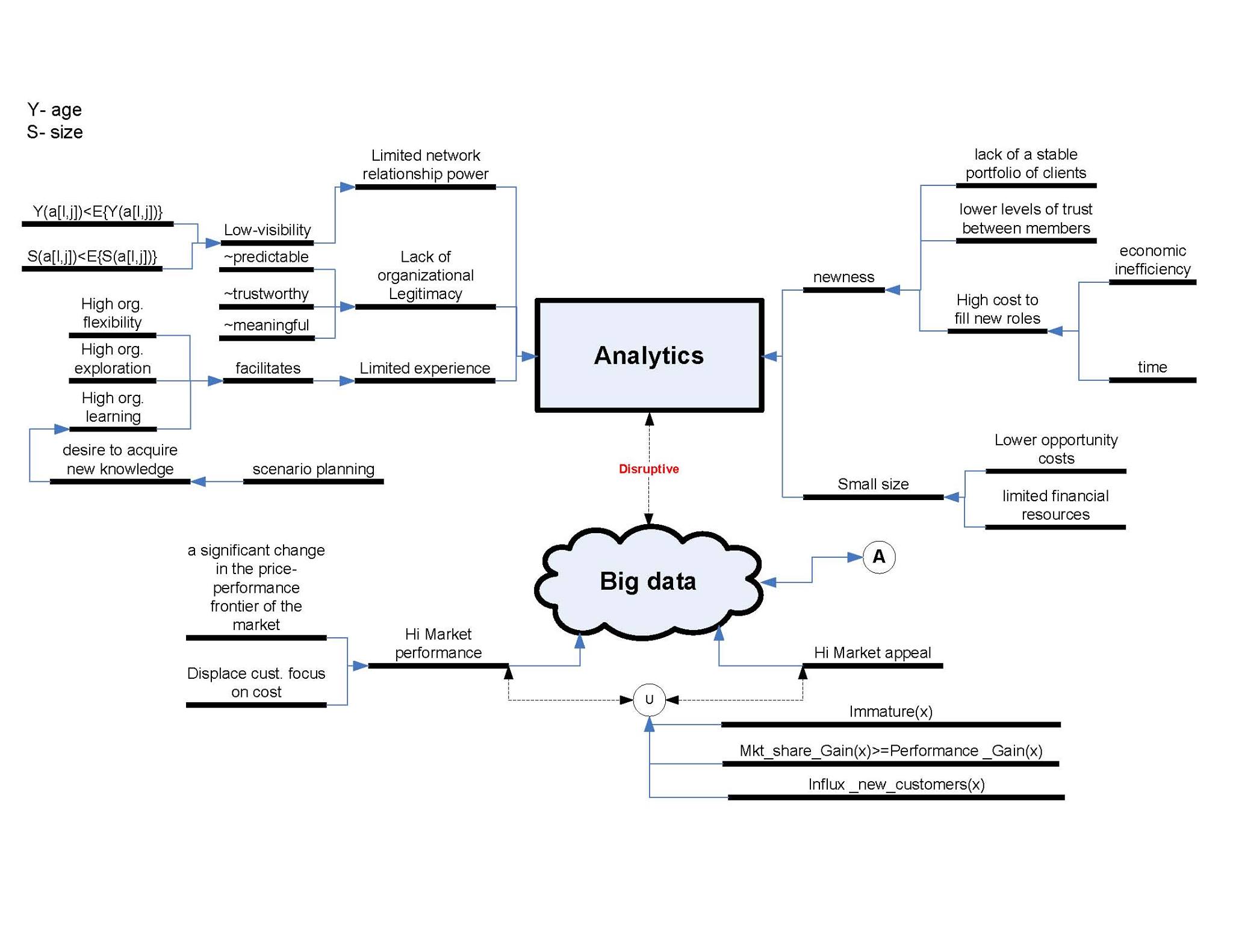

Modern enterprises have used analytics to extract useful, managerial insights from big data that have resulted in a sustained competitive advantage. When integrated into the decision-making process of a firm, analytics has been credited with improving the quality of business decisions. There have been increased instances when business analytics has enriched managers’ roles in those situations where they were constantly faced with making an excessive amount of decisions on a daily basis when using the analytical tools pertinent to personal loan approval systems, airline and hotel pricing systems, as well as supply chain optimizers. Effectively, managers have become even more empowered when their roles evolved from an operational level to a decision-making one; thus making the human a supervisor of a complex set of operations. Bell (2008) stated that the most promising outcome from the combination of analytics and big data has been the spawning of new business models. Such models have made it easy for firms to segment markets based on the needs of the individual consumer thereby creating more opportunities for niche businesses.

The proliferation of falling prices and increased functionalities in technology has made it easier for the modern firm to leverage the business model and offer greater value to its customer base. For instance in the case of APPLE’s iTunes software and website, the success of the site has depended on the morphing of its service offerings from selling music to offering the customer more choice in its product delivery, by using a business model that allowed each of the choices to reinforce one another (Osterwalder, Pigneur and Tucci, 2005). Post 20th century, technology has been the key driver in shaping the fit and type of business models used. In reality, business models have been employed mainly to enhance the technology’s capability to maximize the firm’s customer outreach at minimal cost. Subsequently, the business model has become the post hoc representation of organizational structural change in the pursuit of the next opportunity (Bock and Bock, 2011, 2012). At the taxonomic level, Bonchek and Choudary (2013) have identified the shift in firms moving away from the traditional pipe business model towards the platform business model since the surge of big data has eroded the traditional benefits of linearity. In the past, pipe business models have operated on the premise of creating value up stream and consuming it downstream. Currently, platform business models have embraced the premise of using a framework that would facilitate trade by coordinating producers with consumers. Such coordination has been using data analytics to improve the stickiness of the framework. In addition, the onset of new technologies has invaded the business model space by making their characteristics fundamental to the business model’s design (Chen, 2009). Get the references cited in this article here at this site by getting the online article on big data here.